TOP STORIES

-

LATEST: Think you’re paying less tax now? The withdrawal of Working and Child Tax Credits leaves low earners paying a 73% marginal tax rate, and medium earners paying even more

...And this government says it cuts taxes for poor working households!

-

RIP-OFF NEWS ROUND-UP, OUR PICK OF THE LAST WEEK'S MEDIA

Drug firm Novartis tried to 'scupper' trials of a cheaper version of eye medicine

Has Austerity caused the UK’s first decline in life expectancy in 20 years?

Kellogg's effectively paid no corporation tax in the UK in 2013, +more stories...

-

YOU'RE FIRED?! We are already nearly the most easily fired people in the developed world

Only the US and Canada make it easier, says the OECD’s Worker Protection Index -

EYE OPENER: Housing Equity Withdrawal took off in 1979. Since then almost all UK growth has suspiciously equalled the amount we took out. Looks like it’s pensions next

Osborne’s new rules allow you to spend your entire pension pot now. Same mistake, different pot -

DID YOU KNOW? MPs are getting a 10% pay hike in May, to £74k

...and in 2010, 137 MPs put family members on parliament's payroll. Now it's soared to 167

CARTOONS

Friday, 30 September 2011

Tuesday, 27 September 2011

Tuesday, September 27, 2011

Posted by Jake

No comments

Labels: energy, insurance, Labour, OFCOM, OFGEM, OFT, politicians, regulation, retailers, sales techniques, transport

Sunday, 25 September 2011

With EDF Energy announcing price hikes in September 2011, the last of the Big Six energy companies joined the syncopated pricing goosestep stamping on the wallets of us ripped-off Britons.

All the companies concurred (surely not colluded?) in their main excuse – price hikes are caused by the rise in wholesale energy prices. We are led to believe that those drilling gas producers and electricity generators are inflicting heavy price rises on the poor old retail energy companies, who struggle to keep our bills down but are ultimately forced to kick them up.

“I know it hurts everyone when we put up prices and I wish we didn’t have to.”

“We understand times are difficult, and we’ve done everything we can to absorb these additional costs for as long as possible.”

EDF justified its September 2011 price hike by showing a graph of the wholesale price since November 2010:

But, like the tantalising dancers of the orient, they are careful not to twitch their veil back a further few months, which embarrassingly for them shows the price had just fallen by an even greater amount.

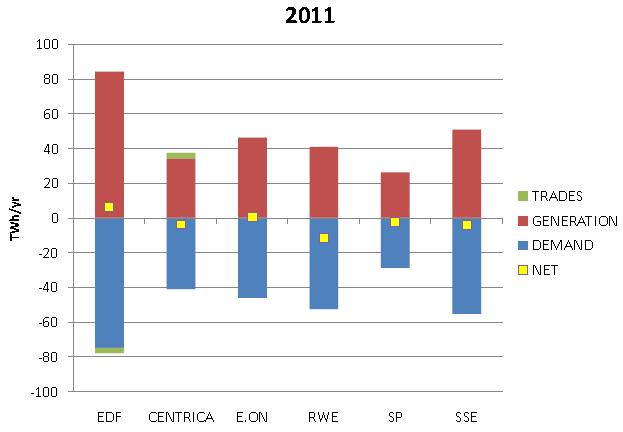

The fact is the retail energy companies, who bill us, buy their wholesale gas and electricity from...you guessed it...themselves. The gouging generators, who snatch the coal and gas from the Earth and generate the wholesale electricity, are the retailers’ own conjoined twins. Each of the ‘big six’ are now able to supply virtually all their own needs. The graph below from OFGEM shows above the zero line how much energy the retail companies' generation twin can generate, and below the zero line how much energy the companies sell to the likes of you and me and the businesses that employ us. All six are more or less in balance – they can supply their own demands. [In the graph, RWE is the owner of nPower, SP is Scottish Power]

Since 2004 the energy industry has simply moved its profits from the retail side of the business to the wholesale generation business. As can be seen from the soaring OFGEM graph below showing the Value Chain Profitability:

Their wholesale arms sell to their retail arms at a high price, allowing their retail arms to blame wholesale prices for them hiking our bills. And allowing them to state with a straight face that they are making tiny margins on their retail business

Npower’s excuse for putting up prices in August was also puzzlingly contradictory. In the same media release they blamed recent events such as the 2011 Arab Spring and the Fukushima reactor meltdown in Japan for pushing wholesale prices up.

"Wholesale energy prices have been impacted by events such as the tsunami and Fukushima in Japan, political changes in the Middle East, nuclear shut down in Germany."

And yet they claim that falls in the wholesale price of energy doesn’t affect bills, because they buy their supplies up to 3 years in advance – in which case recent events should be irrelevant.

"Recent media coverage has reported that wholesale energy prices on the ‘Spot Market’ have fallen - this is correct. However, energy suppliers buy in advance, in some cases up to three years; they do not buy all their energy a day or a month ahead from when they require it. Therefore changes on the short term ‘spot market’ have very little impact. npower has already bought a significant proportion of its needs for customers to cover the coming winter period."

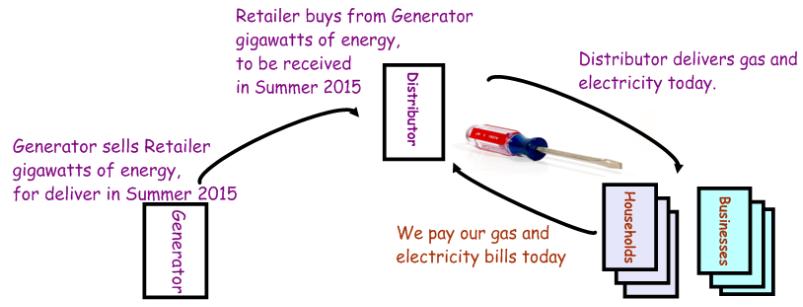

The futures market is a vital part of maintaining price predictability – important to business Britain and domestic Britain. So, when the energy companies blame the cost of energy they bought 3 years ago for putting up prices today, what do they mean?

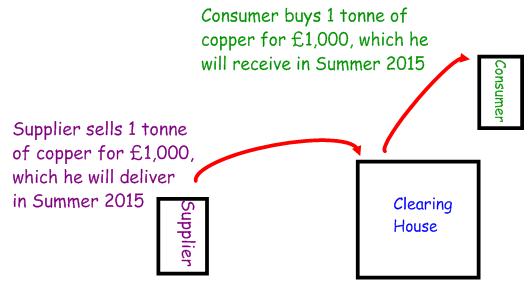

In a well regulated futures market, such as the market for industrial metals including copper, things work pretty much as they should. Consider a futures trade, in which one tonne of copper is bought to be delivered a couple of years in the future:

The futures contract fixes the price of the copper - a guaranteed price for something that will be delivered in the future. This gives certainty to the Supplier and the Consumer so that they won't be harmed by significant price changes in the months or years until the copper is delivered. The consumer, perhaps a builder putting up a big condominium complex, won't get round to wiring the building until the structure is put up which will take a year. He wants to know what the copper wire will cost him, so he can put a price on the condominiums and start pre-selling them before building is complete.

To avoid the risk of either the supplier or the consumer going out of business in the months or years and not being around to complete the delivery of and full payment for the copper, the contracts are transferred to a central Clearing House. The way this works is:

- Originally, the Supplier was contracted to deliver to the Consumer, and the Consumer was contracted to pay the Supplier.

- Now the Supplier is contracted to deliver to the Clearing House, and the Consumer is contracted to take delivery from the Clearing House.

The Clearing House takes margin payments from Supplier and Consumer, and is strong enough to absorb any defaults. The Clearing House also maintains a balance between all contracts from thousands of counterparties - contracts to deliver and contracts to receive balance out - so it is unlikely to ever have to supply or take delivery of any copper.

The Clearing House takes margin payments from Supplier and Consumer, and is strong enough to absorb any defaults. The Clearing House also maintains a balance between all contracts from thousands of counterparties - contracts to deliver and contracts to receive balance out - so it is unlikely to ever have to supply or take delivery of any copper.

If the price of copper starts falling, say to £900 on the delivery date, this is good for the Supplier, who still gets £1,000.

If the Consumer thinks the price will continue to fall, and so doesn't want the £1,000 copper anymore, believing he can buy later at an even lower price as copper continues to fall, he sells copper at the current price of £900 to another trader (freezing the Consumer's losses at £100). The trader is confident he can unload this at a profit later.

This new contract is also transferred to the Clearing House.

The Consumer now has two contracts with the Clearing House

1) To buy 1 tonne of copper in Summer 2015 at £1,000

2) To sell 1 tonne of copper in Summer 2015 at £900

These two contracts cancel each other out. The Consumer is off the hook, taking a £100 loss but now able to benefit from further falls in the price of copper.

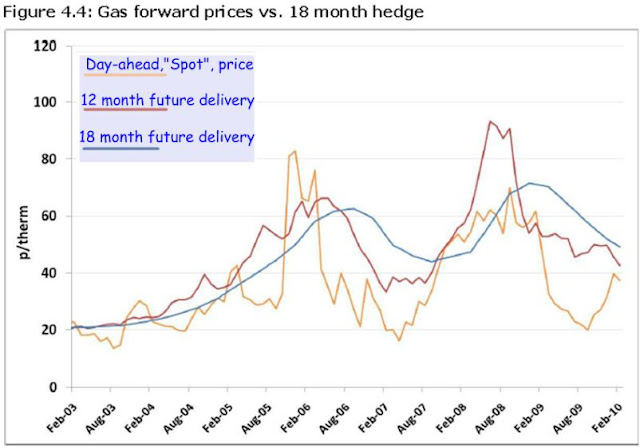

The "spot price", also called the "day-ahead" price, is the true reflection of supply and demand today. The "futures" price is a trader's guess of what the supply and demand will be in the future... or an energy company executive's guess of what OFGEM will let him get away with!

So, what is the impact of all this energy-trading? According to an OFGEM report, since the energy companies switched their profits from their retail business to their generation business in 2005, the energy retailers are typically paying the energy wholesalers twice the true current supply&demand "spot", or "day-ahead", price.

Of course, they are paying this inflated price to themselves. So they're all right. But what about the rest of us?

Friday, 23 September 2011

Friday, September 23, 2011

Posted by Jake

No comments

Labels: Bank of England, banks, Big Society, credit crunch, inequality

Monday, 19 September 2011

Saturday, 17 September 2011

Saturday, September 17, 2011

Posted by Jake

5 comments

Labels: Article, banks, Bonus, British Bankers Assoc, pay, taxation

We judge doctors not by their own health, but by the health of their customers - their patients.

We judge teachers not by their own erudition, but by the accomplishments of their customers - their students.

Why is it that we judge bankers by their own wealth, and not by the wealth of their customers - us?

Why does Britain celebrate, nurture and protect the wealth of bankers, while putting up with miserable investment returns, pitiless rip-offs, and economy crushing bank-bailouts?

Rip-offs in the financial sector, such as the Great Payment Protection Insurance Scam, have triggered a landslide of rip-offs in the rest of the economy. With the bankers having set the pace, executives in other industries greedily follow. Their logic being:

- Bankers are paid loads more than me

- I am as valuable as a banker

- I should be paid loads more than I am

Forgetting that highwaymen don’t take your money because they are worth it but because they can, they overlook the other logical conclusion:

- Bankers are paid loads more than me

- I am as valuable as a banker

- They should be paid loads less than they are

Executives across the land quickly realised the easiest way they can keep up with the bankers is to join in the ripping-off. Energy companies pushing up prices in-spite of record profits; telecoms companies fibbing about broadband speeds; suppliers ripping-off the government charging £22 for a 65p lightbulb. Even our much loved family doctors, finer fellows than those bankers, made a successful grab for a bumper payrise with a cunningly negotiated contract.

National Audit Office, review of GP contracts, 28th February 2008

Bankers give one single prime reason for “having” to pay themselves grotesque salaries. They plead the need to recruit and retain the best of the best, to stem the 'talent drain'. Bankers argue that if it weren’t for the risk of them being tempted away by other even more grotesque salaries, they wouldn’t be forced into being so grotesque about paying themselves. It's not their own fault, it's the other bankers' fault.

So, is all this business about ‘the best of the best’ actually true? We can use mathematics, in the form of basic "teenager level" probability theory, to reveal all. With the help of some baboons, pictures compliments of the Wikimedia Commons, and some tweaking by ourselves.

If 100 baboons entered a contest to play a Bach fugue on the piano, would half of them be better than average? The maths will reveal all about both baboons and bankers.

Answer: Yes, assuming they all have to be ranked separately, i.e. they can’t all be judged “equally (in)competent”. (Mathematical pedants would point out that if one baboon was judged to be first, and the other 99 to be equal second, then only one baboon would be above average).

Under these conditions, assuming all the monkeys were roughly equally skilled, and their ranking in the contest was just random chance, the chances of a baboon getting into the top 50% three times in a row would be one chance in eight, or 12.5% (maths is explained a little further down).

Now, lets compare the baboons with fund managers. “Masters of the Universe” who claim that they must be paid fabulous money because they are so excellent. What do their actual results say? Like the best athletes you would have thought the ‘best’ bankers would be able to get at least into the top quarter almost every time.

Using pure random chance, equivalent to a baboon, the probability of coming in the top quarter of a group is

Compare this with the actual performance of the funds, using Thames River’s Fund Watch which monitors how consistently funds perform:

Just 16 funds out of 1,188 in the Thames River figures for the first quarter of 2011 made it into the top 25% three years in a row. That’s 1.3%, which is close to what you would expect from pure random chance.

Let’s lower the bar. Forget top 25%, surely the ‘best of the best’ can get into the top 50% three years in a row? Looking at the Thames River figures, just 8.6% of funds achieved this.

Let’s compare this with pure random chance:

Again, we see the fund managers achieving something worse than random chance.

Perhaps the fund managers don’t stay ahead of the pack because they are all equally excellent? If that were so

- Why are returns on investments and interest paid on savings so pathetic?

- Why do they plunge the world into financial crisis a couple of times every decade?

But let’s work on that theory in any case. After all, if all tennis players were as superb as Rafael Nadal (number 1 in the world for much of 2010/2011), then the probability of any one of them getting into the top half of the rankings would also be 50%.

To know if all the bankers are veritable battalions of banking Nadals, we only need to measure them against all the other ordinary investors – including the likes of you and me. This can be done by comparing them with the stock market indices, which indicates the average for all investors.

The Standard & Poor’s Index vs Active Funds (SPIVA) report shows that overall, actively managed funds do no better than the stock market index trackers. In fact, the overall statistics show that over a period of 5 years, Index Tracking beats the great majority of actively managed funds. The SPIVA report for North American funds in the year 2008, covering the period before and during the crash of that year, is particularly telling, stating:

· Over the five year market cycle from 2004 to 2008, S&P 500 outperformed 71.9% of actively managed large cap funds, S&P MidCap 400 outperformed 79.1% of mid cap funds and S&P SmallCap 600 outperformed 85.5% of small cap funds. These results are similar to that of the previous five year cycle from 1999 to 2003.

· The belief that bear markets favour active management is a myth. A majority of active funds in eight of the nine domestic equity style boxes were outperformed by indices in the negative markets of 2008. The bear market of 2000 to 2002 showed similar outcomes.

· Benchmark indices outperformed a majority of actively managed fixed income funds in all categories over a five-year horizon. Five year benchmark shortfall ranges from 2-3% per annum for municipal bond funds to 1-5% per annum for investment grade bond funds.

· The script was similar for non-U.S. equity funds, with indices outperforming a majority of actively managed non-U.S. equity funds over the past five years

The scorecards for 2009 and 2010 show similar results, with actively managed funds doing painfully averagely. Index funds that can be administered by a trainee accountant on £25k a year, simply tracking the market indices – such as the FTSE100, S&P500, and the like – performs as well as the multimillionaire fund managers.

So, we see that

a) there is no ‘best of the best’. Fund manager performance matches what you would get from random chance.

b) Fund manager performance overall does worse than the average for the whole markets overall.

With fund managers all much of a muchness, there is no valid reason that would benefit us customers to tempt them with pots of money away from other banks. There is only a need to pay them amounts of money to compete with other professions that may tempt him away from banking. So, how much would that be?

- Drop his pay from £1million to £500,000 and the banker could be tempted away to play in a premier league football team. If he had the talent.

- Drop his pay from £1million to £250,000, and the banker could be tempted away to be a consultant surgeon in one of the London hospitals. If he had the talent.

- Drop his pay from £1million to £125,000, and the banker could be tempted away to sit in the chair of a professor of theoretical physics at Cambridge. If he had the talent.

- Drop his pay from £1million to £62,500, and the banker could be tempted away to be a programmer in a software company. If he had the talent.

- Drop his pay from £1million to £31,250, and the banker could be tempted away to be a teacher in an inner-city comprehensive school. If he had the talent.

The statistics show no evidence that bankers are the best, and a history of boom and bust suggests that they are more Calamity Janes and Crisis Joes. In-spite of this the FSA revealed that more than 2,800 people in the City of London’s financial sector took home more than £1million in 2009.

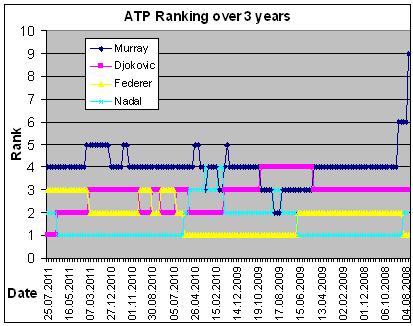

To see what ‘best of the best’ actually means, look at other high profile professions. Take tennis as an example. The top four tennis players as at July 2011 are Djokovic; Nadal; Federer; Murray. Of these four, only Andy Murray has fallen below 4th place in the last 3 years – and even he stayed in the top 10 for that whole period.

These four players have earned career average annual prizes of between US$3million and US$5million.

Compare that with 2,800 bankers in London took home more than £1m (US$1.6) in 2009.

Then compare the bankers with the ATP tennis players. The amount of prize money earned in 2011 up to the end of July by the 1,800th ranked player (close to the last in the list) was US$519. Five hundred and nineteen dollars.

To earn that US$519, the player was 1,000 places higher than one of those 2,800 City bankers paid £1m or more.

To earn that US$519, the player was 1,000 places higher than one of those 2,800 City bankers paid £1m or more.Of course, bankers’ pay could be cut to a fraction of what it is now, and they would have nowhere to go. The reality is that bankers look after themselves first. Moderating pay policies won’t happen without outside intervention.

There is a precedent. The law discourages individuals from mugging people in the streets and burglarising citizens’ houses. Excessive fees and charges, which pay for excessive bankers pay, are no different from mugging and burglary. Pinching citizens’ property, in the form of their savings and investments: up to 50% of a working lifetime’s saving into a pension can go in charges.

In the end, bankers can’t keep up their pay alone. It needs a combination of the cupidity of other bankers, the cowardliness of politicians, and the complicity of regulators.

In the end, bankers can’t keep up their pay alone. It needs a combination of the cupidity of other bankers, the cowardliness of politicians, and the complicity of regulators. And, perhaps most of all, the complacency of the rest of us.

The “Arab Awakening”, ordinary people protesting in the streets, brought down in months oppressive regimes that had lasted decades. How about a “Ripped-Off Briton awakening”?

Dealing with excessive pay in the financial services would be a victory against rip-offs across Britain in every sector.

Friday, 16 September 2011

Friday, September 16, 2011

Posted by Jake

No comments

Labels: budget cuts, inequality, Inflation, transport

The Dept of Transport does, in fact, have a special budget for a strategy to ease overcrowding. Chris and KJ realise the problem may now solve itself...

Tuesday, 13 September 2011

Tuesday, September 13, 2011

Posted by Jake

No comments

Labels: banks, British Bankers Assoc, budget cuts, credit crunch, FSA, inequality, jobs, Osborne, regulation, taxation

Monday, 12 September 2011

Monday, September 12, 2011

Posted by Jake

4 comments

Labels: Article, Guest, Inflation, regulation, the government, transport

By Alexandra Woodsworth,campaigner at Campaign for Better Transport.

Britons are already some of the most ripped-off in the world when it comes to rail fares. The UK’s railway is fragmented and up to 40% less efficient than its European counterparts, making it highly expensive to run. Passengers are paying the price for this inefficiency. Fares have been steadily increasing over the past twenty years, with some season tickets now costing the equivalent of a fifth of the average UK salary – and unfortunately it’s set to get much worse.

The government has decided to raise the cap on regulated rail fares from 1% above the RPI inflation rate to 3% above RPI from January 2012. Inflation is still running high, which means that tickets are on course to rise by 28% over the next four years, or over £1,300 more for some season tickets. With millions of workers facing pay freezes, rail fares are now increasing four times faster than wages – making the cost of doing a day’s work increasingly unbearable.

Government figures show that the planned fare increases from 2012 are likely to result in fewer people using the train. Instead of managing the railways as an essential public service, open to everyone, trains are in danger of becoming a luxury affordable only to the rich.

This isn’t just a problem for fed-up passengers. Access by affordable public transport to limited jobs is essential to the health of the UK economy, and reducing this access undermines the Government’s objectives of getting people back into work. We are running the risk of pricing people out of the labour market in London and our other major cities, and damaging the UK’s competitiveness in a global marketplace. Claims of ‘green government’ are also ringing hollow, as – even with high petrol prices – driving becomes the cheaper option than going by train.

The Government says that these fare rises are needed to pay for investment in new trains and other improvements. But in most cases, passengers are paying vast sums now for changes that are many years off, or will in fact never see the benefits because the investment is taking place on routes they never use. At any rate, this is a spurious argument: the improvements the government has committed to are already in the budget. In reality, raising fares is an austerity measure designed to reduce government spending on the railways, and shift the burden further onto fare-paying passengers. In recent years, the split has been about 50/50, and the government has said that passengers should pay 75%. But with fares already rising above inflation each year, the government’s contribution is falling steadily, and the chart below shows that we are on course to reach the government’s target, without the need to lift the cap to RPI+3%.

Source: Realising the Potential of GB Rail: Final Independent Report of the Rail Value for Money Study (McNulty review), May 2011. http://www.dft.gov.uk/publications/realising-the-potential-of-gb-rail/

So how can these hikes be justified? Some scream that taxpayers shouldn’t pay a penny towards a service they don’t use. These critics conveniently overlook the fact that public services like the railways don’t only provide benefits to those who use them. Railways provide a host of social and environmental goods, and help to deliver a range of the government’s objectives, that must be recognised when addressing the question of who should fund them. This is recognised by many of our European counterparts, where state support has helped to create modern, efficient, affordable railways.

Here in the UK, fares regulation – established to protect passengers from the profit motive of private companies, and ensure affordable travel by public transport – has been turned on its head and is being used to make money for a government that promised fair fares when it came to power. Just how much money is currently impossible to fathom. The rules on fares and funding are labyrinthine and not understood even by industry experts, and fare revenue data (how much is raised, on what routes, and who it goes to) is deliberately withheld from public access, making it impossible to hold both government and train companies to account. And passengers facing huge hikes in regulated fares shouldn’t look to the train companies to be magnanimous and fill the gap by providing other kinds of affordable tickets – historically, unregulated fares have risen much more sharply than regulated tickets.

Squeezed in the middle, passengers are rightly outraged; not only at what rising fares will do to their household finances, but because they don’t seem to be getting anything in return. Overcrowding, delayed and cancelled trains, cruel and unusual penalty fines – it’s all bad enough, let alone having to pay hundreds of pounds more each year in return for the privilege of being packed like a sardine on a train that often won’t even get you to work on time.

Commuters more used to muttering under their breath or firing off a sarky tweet are being galvanised. Over the summer, they descended in their hundreds on train stations across the country, protesting for fair fares and gathering signatures on a petition demanding that the government reverse the planned fare hikes. But the true commuter rage is likely to be seen in January, when passengers turn up at the ticket office and find out just how much more they’re being ripped off this time.

Commuters more used to muttering under their breath or firing off a sarky tweet are being galvanised. Over the summer, they descended in their hundreds on train stations across the country, protesting for fair fares and gathering signatures on a petition demanding that the government reverse the planned fare hikes. But the true commuter rage is likely to be seen in January, when passengers turn up at the ticket office and find out just how much more they’re being ripped off this time.Join the campaign at www.fairfaresnow.org.uk

Alexandra Woodsworth is public transport campaigner at Campaign for Better Transport.

Thursday, 8 September 2011

By Deborah Hargreaves, Chair of the High Pay Commission

By 2030, Britain will be back to levels of inequality last seen in the Victorian era if pay trends go unchallenged. The High Pay Commission’s recent interim report found that the top 0.1 per cent of earners will take home 10 per cent of national income by 2025 and 14 per cent by 2030 on the present trajectory.

The public is angry about the yawning gap that has opened up between rich and poor. In an ICM poll for the commission, 72 per cent of those questioned felt that high pay made Britain grossly unequal. Concerns are legitimate. FTSE 100 bosses are paid 145 times the average wage and, on current trends, this would rise to 214 times by 2020. Corporate leaders have seen their pay quadruple in the past 10 years, while average earnings increased at just 0.1 per cent a year.

Meanwhile, share prices dropped. This decoupling between pay and company performance is of great concern. In the poll, 73 per cent said they had no faith in business or government to tackle excessive pay.

There are strong moral arguments to make against inequality, not least that it creates an elite with access to a range of high-end private services and little concept of the difficulties faced by the public during economic austerity. But there is also a strong economic argument against devoting the lion’s share of rewards to those at the top: it is a very inefficient allocation of resources. Wealthy people tend to save more of their income, which means there is little trickle-down to the rest of society. If the spoils were divided more equally, those in the “squeezed middle” would spend more and help get the economy back on its feet.

Several factors have contributed to the arms race in pay at the top. Perhaps surprisingly, some corporate governance reforms introduced to improve executive accountability to shareholders appear to have pushed pay up. For example, publication of data on executive packages has seen the growth of an industry devoted to comparing pay levels. This means executives can demand they earn as much as rivals and remuneration committees aim to be in the top quartile for pay. That is not to say we should have less disclosure, only that it could be done better.

At the same time, attempts to link executive pay to company performance by increasing the discretionary portion of business leaders’ packages appear to have led to ever-rising awards. In return for accepting performance-linked packages, executives seem to have demanded compensating increases in base salary.

Performance elements of the package have also increased sharply. Last year, the average top award that could be achieved under all share-based incentive schemes in the FTSE 100 was 328 per cent of salary compared with 174 per cent in 2006.

At the High Pay Commission we suspect that performance-linked incentives are a lot weaker than claimed, with many designed to pay out in too broad a range of circumstances. We are conducting our own research this summer into the issue.

[Latest publication 6th Sep 2011: "What are we paying for: Exploring executive pay and performance"]

We believe that reforms to challenge the inexorable rise of top pay are overdue and this is echoed by a growing public backlash. In fact, our interviews with top earners have often thrown up suggestions that the system is unsustainable and should be tackled. But insiders appear reluctant to break rank.

A range of options could be brought forward. Reform of remuneration committees is a compelling idea that is gaining momentum. Elections to the remuneration committee, and particularly the inclusion of employee representatives, could shine some light on the process and put a brake on awards.

We back the publication of pay ratios – top bosses to median pay – as advocated by Will Hutton’s review of public sector pay. If disclosed in a uniform way, these could inform the debate. However, the imposition of a statutory ratio on companies could have adverse consequences such as the outsourcing of low-paid jobs.

More important for shareholders is the simplification of executive packages. These have become so complex that they are difficult to understand, require a lot of investors’ time and remain opaque. What is wrong with a base salary along with some share incentive? If shares were held until retirement or resignation, that would provide a long-term focus for the executive.

These are all areas we will be looking at in detail over the coming months; any proposals will need to be tested carefully. But we are concerned that the laissez-faire approach of the past 10 years has become unsustainable and believe action is required.

Deborah Hargreaves is chair of the High Pay Commission

The public is angry about the yawning gap that has opened up between rich and poor. In an ICM poll for the commission, 72 per cent of those questioned felt that high pay made Britain grossly unequal. Concerns are legitimate. FTSE 100 bosses are paid 145 times the average wage and, on current trends, this would rise to 214 times by 2020. Corporate leaders have seen their pay quadruple in the past 10 years, while average earnings increased at just 0.1 per cent a year.

Meanwhile, share prices dropped. This decoupling between pay and company performance is of great concern. In the poll, 73 per cent said they had no faith in business or government to tackle excessive pay.

There are strong moral arguments to make against inequality, not least that it creates an elite with access to a range of high-end private services and little concept of the difficulties faced by the public during economic austerity. But there is also a strong economic argument against devoting the lion’s share of rewards to those at the top: it is a very inefficient allocation of resources. Wealthy people tend to save more of their income, which means there is little trickle-down to the rest of society. If the spoils were divided more equally, those in the “squeezed middle” would spend more and help get the economy back on its feet.

Several factors have contributed to the arms race in pay at the top. Perhaps surprisingly, some corporate governance reforms introduced to improve executive accountability to shareholders appear to have pushed pay up. For example, publication of data on executive packages has seen the growth of an industry devoted to comparing pay levels. This means executives can demand they earn as much as rivals and remuneration committees aim to be in the top quartile for pay. That is not to say we should have less disclosure, only that it could be done better.

At the same time, attempts to link executive pay to company performance by increasing the discretionary portion of business leaders’ packages appear to have led to ever-rising awards. In return for accepting performance-linked packages, executives seem to have demanded compensating increases in base salary.

Performance elements of the package have also increased sharply. Last year, the average top award that could be achieved under all share-based incentive schemes in the FTSE 100 was 328 per cent of salary compared with 174 per cent in 2006.

At the High Pay Commission we suspect that performance-linked incentives are a lot weaker than claimed, with many designed to pay out in too broad a range of circumstances. We are conducting our own research this summer into the issue.

[Latest publication 6th Sep 2011: "What are we paying for: Exploring executive pay and performance"]

We believe that reforms to challenge the inexorable rise of top pay are overdue and this is echoed by a growing public backlash. In fact, our interviews with top earners have often thrown up suggestions that the system is unsustainable and should be tackled. But insiders appear reluctant to break rank.

A range of options could be brought forward. Reform of remuneration committees is a compelling idea that is gaining momentum. Elections to the remuneration committee, and particularly the inclusion of employee representatives, could shine some light on the process and put a brake on awards.

We back the publication of pay ratios – top bosses to median pay – as advocated by Will Hutton’s review of public sector pay. If disclosed in a uniform way, these could inform the debate. However, the imposition of a statutory ratio on companies could have adverse consequences such as the outsourcing of low-paid jobs.

More important for shareholders is the simplification of executive packages. These have become so complex that they are difficult to understand, require a lot of investors’ time and remain opaque. What is wrong with a base salary along with some share incentive? If shares were held until retirement or resignation, that would provide a long-term focus for the executive.

These are all areas we will be looking at in detail over the coming months; any proposals will need to be tested carefully. But we are concerned that the laissez-faire approach of the past 10 years has become unsustainable and believe action is required.

Deborah Hargreaves is chair of the High Pay Commission

This article first appeared in Financial World, the monthly magazine of ifs School of Finance, which is produced by the CSFI think-tank.

Thursday, September 08, 2011

Posted by Jake

No comments

Labels: budget cuts, credit crunch, inequality, MP, pay, taxation, Tories

Thursday, 1 September 2011

Thursday, September 01, 2011

Posted by Jake

8 comments

Labels: Article, banks, British Bankers Assoc, credit crunch, inequality, Vince

The director general of the Confederation of British Industry in an interview on Radio 4’s Today Programme, on 31/8/2011, commented that all the “over 240,000” members of the CBI – who come from just about every industry in Britain from banking to bolt-making – oppose plans to reform bank regulation at this time.

When Evan Davis, presenter of the Today Programme, suggested the CBI director general, John Cridland, is a paid spokesman for the banks, Cridland responded:

Reforms that Cridland describes as “barking mad”. To suggest there is “no division” for such a diverse group smacks of a North Korean election result. Perhaps it reflects the fact that the CBI’s idea of representation bears the hallmarks of the advisory panel of the Dear Leader, Kim Jong Il, which includes his long dead dear dad Kim Il-Sung in his role of “Eternal President”. As can be seen by the constitution of its Charimen's Committee which drives CBI’s policy:

- According to the CBI website, the CBI Chairmen’s Committee “takes the lead responsibility for setting the CBI's position on all policy matters” and comprises at least 10% representing SMEs.

- Government stats show that small and medium enterprises (SMEs) represent “99.9 per cent of all enterprises, 59.8 per cent of private sector employment and 49.0 per cent of private sector turnover”

Evidently small and medium businesses are poorly represented on the policy making committee of the CBI. The key point of contention the CBI has joined up with the British Bankers Association to oppose is the ‘ring-fencing of retail banks’.

The big banks and their acolytes have a whole legion of reasons why ring-fencing is not a good idea. Their pronouncements go on about how things will be worse and more expensive for the likes of you and me and the butcher, baker and candlestick maker. Commentators from august organs such as the Financial Times deny this. But they are not paid to bang on about it, lobbying, dissembling, and generally propagandising as their day-jobs. So it is the banks’ well paid voices that prevail, most importantly in Conservative Central Office.

Two key reasons why the banks don’t like the ring-fence:

- It takes away one of the dirt-cheap ways they have of raising money to bet on risky investments: our deposits. The money from our monthly salaries and our saving, for which they pay us around 0.1% interest – and charge many of us £100s per annum for the privilege.

- So long as their Investment Bank is tied to their Retail Bank, there will be an implicit guarantee that they will never go bust – the taxpayer will save them. This also brings down the cost of borrowing for the banks, because lenders to the bank know even in the worst case they will get their money back from the taxpayers.

Two things that boost the banks’ profitability. Bankers’ bonuses up, but we still get our measly 0.1% interest on our savings.

So what is the ringfencing all about?

If people can't pay back their loans, (a mortgage or business crisis, or a country defaulting on its loans), or the bank's own proprietary investments fall then the banks’ assets fall, threatening the gap between assets and liabilities.

The Equity Capital (money raised by the bank by selling its own shares) is the buffer to keep total Assets more than total Liabilities - so people can get their deposits back if they want to.

The Equity Capital (money raised by the bank by selling its own shares) is the buffer to keep total Assets more than total Liabilities - so people can get their deposits back if they want to.

If things get even worse, then the bank must either raise more capital or go bust. During the Credit Crisis banks couldn't raise capital because they were so clearly busted not even other banks were daft enough to invest in them, so it was left to the taxpayer to bail them out. Taxpayer money was injected into banks around the world to bring the banks’ assets back above their liabilities.

What this means, in plain English, is that taxpayers' money was paid to the banks to cover their losses - whether losses came from lending to home-owners and businesses, or from speculating in the casino of derivatives, equities, and whatever.

What this means, in plain English, is that taxpayers' money was paid to the banks to cover their losses - whether losses came from lending to home-owners and businesses, or from speculating in the casino of derivatives, equities, and whatever.

Ring-fencing retail banks basically means:

· They must maintain a larger equity capital buffer

· They must not get involved in higher risk activities

This graphic from the IBC’s Interim Report provides an outline of where the ring-fence lies. All retail deposits - your and my savings - are held within the ring-fence.

The current situation is like having a high risk boy-racer (the investment banker) driving a bus with all us ordinary citizens in it. The boy-racer gets his multi-million bonuses, while us passengers collect our 0.1% interest on deposits. When the racer crashes – as we have seen with painful regularity over the last few decades – everyone gets injured. Though the driver generally has an air-bag stuffed with his previous years’ bonuses.

Ring-fencing will put a more cautious driver on the bus, and let the boy-racer take his risks in his go-kart. The cautious driver is less likely to have an accident, the damage from any accident that does happen is likely to be less severe – so we the taxpayers are prepared to insure the bus. When the boy-racer crashes, the victims are those who were seduced into the risk by his furry dice and go-faster stripes. Who knows – take away the investment banks' taxpayer funded airbags, and even they may drive less foolishly.

The ring-fenced retail banks are less risky. But in the less likely event they need rescuing, it will cost the taxpayer far less than the £850billion it cost the UK taxpayer in 2008. A bill paid for by cuts in defence, education, health, and just about everything else - except bankers' bonuses.

Since the 2010 election, Tories have appeared to be more even handed than in their Nasty Party past. But is their benevolent smile actually a rictus grin carved by their Liberal-Democrat bedfellows, in particular Vince Cable? And does their apparent intention to postpone any regulatory change to after the next election in 2015 reveal their hope that the Lib-Dems will be wiped out? And with it the forced Tory grin relaxing back into its customary snarl?

I hope not, but think so.

Follow Us

Search Us

Trending

Labels

advertising

Article

Austerity

Bank of England

banks

benefits

Big Society

BIJ

Bonus

British Bankers Assoc

budget cuts

Cameron

CBI

Clegg

Comment

credit crunch

defence

education

elections

energy

environment

executive

expense fraud

FCA

FFS

FSA

Gove

Graphs

Guest

HMRC

housing

immigration

inequality

Inflation

insurance

jobs

Labour

leisure

LibDems

Liebrary

Manufacturing

media

Miliband

MP

NHS

OFCOM

Offshore

OFGEM

OFT

Osborne

outsourcing

pay

pensions

pharma

police

politicians

Poll

Priority

property

protests

public sector

Puppets

Ready

regulation

retailers

Roundup

sales techniques

series

SFO

sports

supermarkets

taxation

Telecoms

the courts

the government

tobacco

Tories

transport

UK Uncut

unions

Vince

water

Archive

-

▼

2011

(185)

-

▼

September

(14)

- The truth about traders

- Labour's fairness pledge for consumers

- Electricity and Gas Bills – how energy companies a...

- The Bank of England heads back to the printers

- Tax consultants fear 'name and shame' policy

- Banker Pay - the mathematical truth behind the 'pa...

- Railway fares and overcrowding

- Banking reforms: a waiting game

- Fares ain't fair: The great rail fare rip-off

- High Pay Commission exposes remuneration trends an...

- Why abolishing the top tax rate is so urgent

- Debit card surcharges: when drip pricing becomes a...

- Ring-Fencing Retail Banks – why it’s barking mad t...

- Using rents to cling to the property ladder

-

▼

September

(14)

Powered by Blogger.